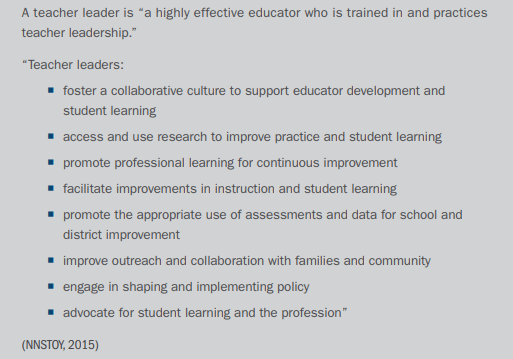

Next to a highly effective teacher, nothing has a greater impact on student learning than a highly effective principal. As the instructional leader in a school, a principal is directly responsible for adult professional learning and growth, which in turn drives increased student achievement.

This is much different than the historical role of a school principal, and the last 10-15 years have seen much change. As such, the role of a principal has transformed from “administrator/building manager” to lead learner and instructional coach. For some, this adaptation pushes on identity, and may not be a welcomed change. For many, the transformed job expectations feel positive and meaningful, yet perhaps still a bit unfamiliar. Adaptation is not always easy, even with high desire.

So exactly how might a principal (or aspiring leader) shift his or her identity to that of lead learner and instructional coach? While acknowledging that each school and person are unique, here are four general, interdependent tips:

1. Lead With Ignorance: That sounds a bit crazy, doesn’t it? What I mean is to never, ever be afraid to show your ignorance about an issue or to learn more about a differing perspective. Ask questions to seek to understand. When you model the trait of an inquiry learner, you demonstrate that no one person is expected to know it all and that multiple perspectives exist. Renowned education researcher Dr. Richard Elmore explains it as follows:

“Effective leaders make their own questioning—hence their own ignorance—visible to those they work with. They ask hard questions about why and how things work or don’t work, and they lead the kind of inquiry that can result in agreement on the organization’s work and its purposes. “

Most of us are used to advocating for our position. Learning to be an inquirer is a paradigm shift. As Peter Senge, Hal Hamilton, and John Kania offer in The Dawn of System Leadership: “Leading with real inquiry is easy to say, but it constitutes a profound developmental journey for passionate advocates.” We have to be intentional and purposeful in this journey.

2. Align Decisions With Organizational Values: Every learning organization should have a set of guiding principles or values and beliefs that are in place for all to see, hear, and internalize. As decisions are made, be they big or small, adaptive leaders work with their teams to align those decisions (and the decision-making process) with the organization’s core values.

It is vital that teachers see an authentic connection between aspirational language and their daily work. Not only does this promote motivation, it also avoids cynicism. When teachers find their work meaningful, a sense of achievement is instilled, and they are empowered to achieve even more (Nautin, The Aligned Organization, 2014).

3. Build Relational Trust and Authentic Space for Teacher Voice: A study done by the Quaglia Institute for School Voice and Aspirations, published in 2016, shows that “less than half (48%) of teachers agree that ‘I have a voice in decision making at school’.” The logical conclusion for a leader is to never make an important decision without input and processing with those who will be impacted.

As Jane Modoono suggests, principals need to say the following out loud to their teachers, and align behaviors to match: “I trust you, and I see you as professionals.” Moreover, improvement won’t happen “if principals can’t take the staff along the journey.” For a short video on building relational trust in a school setting, check out the thoughts of researcher Dr. Vivanne Robinson.

4. Grow Publicly: In professional learning with Carolyn McKanders from Thinking Collaborative, I first heard the phrase “be willing to grow publicly as a leader.” It resonated with me, and has great interplay with “lead with ignorance.”

Being vulnerable with those around us is not easy, nor does it necessarily come naturally. Many of us feel as if our presence must always be strong, confident, and error-free. Please consider an alternative — researcher and author Dr. Brene Brown describes vulnerability as a courageous act of leadership. Indeed, she believes that groups are “hungry for people who have the courage to say, ‘I need help’ or ‘I own that mistake’.”

The impact on those around us is detailed by Stanford University’s Dr. Emma Seppala:

“Why do we feel more comfortable around someone who is authentic and vulnerable? Because we are particularly sensitive to signs of trustworthiness in our leaders. Servant leadership, for example, which is characterized by authenticity and values-based leadership, yields more positive and constructive behavior in employees and greater feelings of hope and trust in both the leader and the organization.”

So, when you think you must always present a strong, unwavering front, remember that displaying vulnerability actually enhances trust in you, your school, and your district.

Join the conversation…what other adaptive tips would you suggest for school leaders?